Everyone has a kind of personal bibliography, either internal or in a file somewhere, a list of books that have shaped our interests and helped make us who we are. I

would like to share my own list with you.

These authors come from my much longer list of favorite books called The

Dictator’s Book Club—if I ever happen to become a dictator or a tenured professor,

these books will be required reading for my subjects.

This list of influences is still very fluid, and if I return to it in ten or five years it may

look very different. At this moment, though, these are the authors who have

shaped my academic interests and my taste in books. The best of them have

changed the way I look at the world and at myself. I’m sure you will already be

familiar with many of them, but if any are new to you, I hope you will someday look

them up and tell me what you think.

Thomas Hardy- I have Dr. Scott Borders to thank for acquainting me with Hardy. He frequently assigns his novels in a few different

classes (I’ve read Jude the Obscure

for him twice), and I got to take a Special Topics class that focused solely on

his novels and poetry. No other novelist of the prolific 19th

century can match Hardy’s ability to combine suspenseful plots with a bold

examination of social issues. My favorite Hardy novels are Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Jude

the Obscure, and The Return of the

Native.

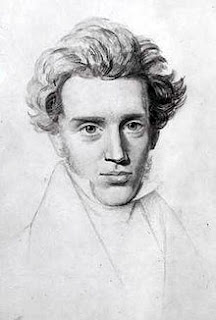

Soren Kierkegaard- I hesitated to include Kierkegaard

because I’ve only started reading his work and because literature

is, of course, superior to philosophy. However, even this brief introduction

has changed the way I think about faith and daily existence, and I see myself

applying his thought to literature and to my life. The most influential works

here are Concluding Unscientific

Postscript and The Sickness unto

Death.

Jane Austen- I’ve loved Austen for a long time, and

my appreciation of her work grows every time I return to it. She is one of the

masters of the craft—her novels are clean and precise, without a sentence or

scene more or less than is needed, and her characters are lively and true. She

had a keen eye for observation and human nature, and her novels can still make us

laugh all these years later. Her best novels are Pride and Prejudice and Emma.

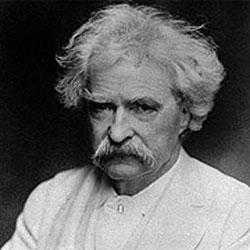

Mark Twain- When I read Austen I remember Elizabeth

Bennet and Emma Woodhouse, but when I read Twain I remember Twain. His

personality is stamped on all of his works, and the treat of reading him is

hearing his wit and humor. But his humor also has a bite. He was a fearless writer

and fierce critic of his own era, and his writing is still challenging for our

own. Huckleberry

Finn is some of his best work, of course, and also Pudd’nhead Wilson and Letters

from the Earth.

Isabel Allende- The

House of the Spirits introduced me to magical realism, a technique/genre

that I have found fascinating ever since. Allende’s work has an emphasis on

story and memorable characters that I’ve always preferred over the better-known

magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. In addition to House of the Spirits, I recommend Eva Luna and The Stories of

Eva Luna.

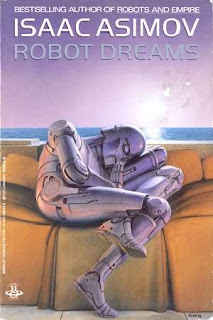

Isaac Asimov- When I first picked up a book of his

short stories, I looked through the first couple pages and immediately

abandoned the other book I had been reading. I find his writing and ideas

fascinating. He is a very pure science fiction writer and his work revolves

around technology and new ideas, but he always considers carefully the personal

and social influence of the technology he imagines. It’s amazing how often he

has been right. His stories “The Last Question,” “The Bicentennial Man,” and “Evidence”

are among the best.

Ursula K. Le Guin- I first picked up a copy of A Wizard of Earthsea in a used book

store sometime early in college. Since then, Le Guin has risen to a secure

second-place spot in my book club. She differs from many of my other favorite

authors by being American and alive. A prolific writer of science

fiction and fantasy, she writes with a more anthropological focus than Asimov.

Her strength is vividly imagining alien worlds as complex and real as our own

and using them to examine social issues and universal humanity. Her books more

than any others have made me rethink my ideas about race and gender, what is

truly human and what is socially constructed, and what is beautiful and fearful about each. My favorites are the Earthsea cycle, The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, and The Birthday of the World and Other Stories.